Tonight We Perform…

Zurück Paula Court

Paula Court

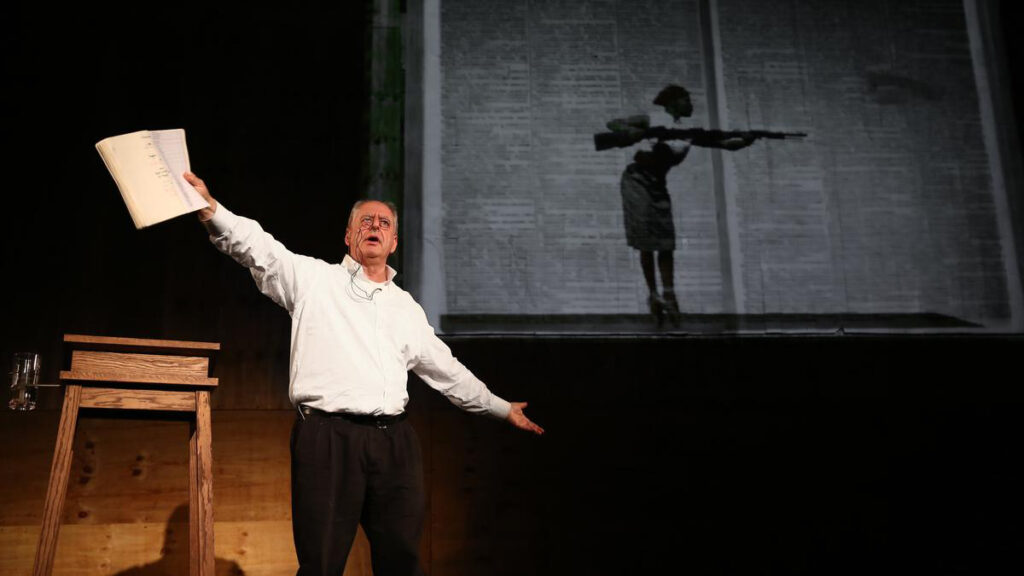

For many years I had made animated films which had been seen by Basil Jones and Adrian Kohler of the Handspring Puppet Company, and they had made puppet theatre which I had seen. We said − let’s see what happens if we put the animation and the puppetry together. Which we finally did a year or so later. We began by testing some fragments of animation I had made, landscapes around Johannesburg, images of a table laying itself. Against these images on a screen we played with a roughly carved wooden puppet that Adrian had carved based on some of the characters that had appeared in some of my films − a woman covered with newspapers, a homeless man in an oversized greatcoat, a businessman in a suit.

We discovered we had a cast of characters and a world for the production but no idea of what play we were performing. We hunted through libraries of play scripts looking for roles for our cast, Myakovsky, Mérimée, Soyinka. In the end we were reduced to Woyzeck as the text that mapped most directly onto what we had done. Our starting point was a disrespect for the text. But as we progressed with the production we discovered that the closer we stuck to the text the stronger the piece was. In the end the play Woyzeck on the Highveld is very faithful to Büchner, but this in spite of us. The inauthentic origins of the project were swamped.

The second production we made, Faustus in Africa!, started as a revenge against Goethe. Take a great European text that has stood reproachfully unread on your bookshelf for 25 years (proclaiming «in here among dead Europeans is true knowledge, too hard for you at the edge of the European gaze») and decimate it, take fragments that make a colonial sense, abandon acres of it. Adrian wanted to try out a new foot and head control for a hyena so a new character was brought into the play. The piece was gradually shaped around the puppets we wanted to make, the pieces of the text that made sense in Johannesburg in 1994 and the chaotic taxonomies of a colonial museum outside Brussels. Which provided the key to the images on the screen. (The screen sometimes functions as scenery − the set in which a scene takes place, a landscape, a café and so on; but more generally it functions as a comment on the thoughts of the characters. A doctor examines Woyzeck’s head with a glass, on the screen we see a representation of the different thoughts of the doctor and Woyzeck.)

The Unwilling Suspension of Disbelief

With Woyzeck we worked with an upper playboard in front of a screen on which animated images were projected using half lifesized rod puppets with a head control in the pelvis of each puppet. The manipulators were hidden by the playboard. We also used a table-height playboard and spent much time and suffering trying to find a way of hiding the manipulators. We hoped to do it with lighting, lighting only the puppets and keeping manipulators in deep shadow. In this we failed and with some embarrassment had to acknowledge that the manipulators (two to a puppet) would be clearly seen by the audience. It was only halfway through the rehearsal period that we realised this was not a liability but an enormously rich part of the performance. For me it was a revelation that the presence of the manipulator not only was not distracting, but was a part of the performance. And this realisation has been at the heart of much of the work we have done since.

There is a triangle of performance. The spectator looks at the actor/manipulator, whose focus is on the puppet. The gaze shifts to the puppet and then returns to the spectator. But returns in a particular way. It is a very conscious return. The spectator is aware he is looking at a double performance, aware of a human hand moving a roughly carved piece of wood, but still cannot stop (when the performance is on track) feeling the transference of the performance from the actor/manipulator to the puppet. You can see Woyzeck being moved to pick up a knife or fork or bottle − but the anxiety this provokes is for the puppet, not for the manipulator. The gaze returns to the spectator in a particular way because the spectator then sits behind himself, observing himself shifting his focus from actor to puppet and back. And one of the pleasures is the pleasure of being aware of the allowing of the transference of the performance to happen. Which happens even if it is resisted. «I will look at the actor not at the puppet.» But the look moves, the performance of the puppet gets its own presence, willingly or unwillingly.

The form itself provokes a layered viewing. When watching an actor or a puppet the activity of viewing is very fractured. Our mind shifts between being held by the performance, being aware of oneself in the theatre, aware of thoughts outside of the performance (things done in the day, things to remember for the next day, ideas and images sparked by something in the play but about something outside of it). With much theatre these shifts of thought are seen as lapses of concentration on the part of the spectator, or faults of the production. The once-removed nature of puppetry makes this layered and shifting viewing of a performance part of the meaning of the hours spent in the theatre.

This working outwards from failure (the failure to cloak the manipulator in shadow) works in other ways too.

The Crocodile’s Mouth

In South Africa at the moment there is a battle between the paper-shredders and the photocopying machines. For each police general who is shredding documents of his past there are officers under him who are photocopying them to keep as insurance against future prosecution. In the production Ubu and the Truth Commission we wanted to show this shredding on stage. But a real machine noisily and slowly going through reams of paper did not seem very remarkable. We considered using a bread-slicer as metaphor but were daunted by the thought of all that sliced bread each evening. I thought of drawing a shredding machine and animating the reams of paper being turned into whorls of spaghetti. Then we thought − we have three dogs on stage − why not feed the evidence to the dogs? But their mouths were too small to swallow a video tape or ream of documents. So we asked, what has a mouthwide enough to swallow a whole dark history?

Hence the crocodile, which became a central character in the play and determined a whole range of the moments and plot directions of the play. Not only puppets and characters, but part of the central story and meaning of the plays often emerges from this type of formal solution to a practical problem. (Our planned three dogs in the end became one. We ran out of manipulators and had to put three heads onto one body, and this too became part of the meaning – three levels of the state apparatus, and the question, if you hang one dog what happens to the other two?)

Good Idea, Handle with Caution

In Monteverdi’s opera Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, there are two major scenes in which three suitors try to woo Penelope. These scenes with their comedy, the action (giving gifts, attempting to draw Ulisse’s bow, the slaughtering of the suitors) and ensemble pieces were what drew me to the opera and made it seem amenable to translation into a puppet work – which eventually materialised in the production Il ritorno d’Ulisse. The solo scenes − more psychological, and static (Penelope’s first lament is fifteen minutes in which nothing moves or changes) − seemed real problems, which I was terrified of and for which I had no solutions. In the end these solo scenes were the most powerful. The scenes in which the double performance of the singers and puppets (triple performance in fact, as there was puppet, primary manipulator and singer, who manipulated the second hand) worked, if not effortlessly, then certainly with a sense of rightness that for me justified the journey of the production. The scenes with the suitors became a question of orchestrating chaos. (For each trio there were nine heads to look at, plus the musicians visible on stage behind the singers.)

I am extremely suspicious of the clear ideas which precede a production. Which is not to say that all are doomed. It is just impossible to tell in advance which ideas are false trails and which will prove fruitful.

Getting up to Speed

The moments to hope for are when the production gets to a critical velocity and the forms and the meanings they bring race along and all one can do is try to keep up. In Ubu, suddenly some of the puppets became two-dimensional – shadow puppets but with white line-drawing on them – initially the line-drawing was to give an outline for Adrian to use in cutting out the cardboard, but we played with filming these cut-outs and this showed a way of animating. From that the whole visual style for the piece emerged.

In Ulisse we needed a frail Ulisse in his bed – the Ulisse of the prologue in which his fate is disputed by L’Humana fragilità, Amore, Fortuna and Tempo, and a heroic Ulisse returning to defeat the suitors. Two Ulisse puppets were made − identical except for a slight gauntness in one. Again we could not keep up with the ideas and possibilities that then emerged.

And one’s reaction when these moments arrive is not to think, what a good idea, how clever we are; but rather, how dumb not to have realised this all along, how dull we are that we have to wait for these ideas or images or ways of working to emerge in spite of rather than because of our plans.

This article was first published in French translation in the magazine Puck, 1998, N° 11.