The Path of Thought: Time and Historical

Zurück City Deep, 2020, Film still, Courtesy of the artist

City Deep, 2020, Film still, Courtesy of the artist

The Path of Thought: Time and Historical Repetition in William Kentridge’s Drawings

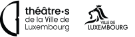

In a central sequence of City Deep, William Kentridge’s new animated film, his first in the Drawings for Projection series for almost a decade, we hear a rushing sound as the Johannesburg Art Gallery crumbles into dust.

Even before this moment of collapse, there is a constant movement in the animation, dissolving and disrupting the drawn lines in each frame. A mouse scuttles across the floor of the museum. A bird flies through the sky, as if tracing a line of thought through the drawing. A fly buzzes across the still life arrangement of fruit. Each drawing is shown constantly trembling on the edge of change. When a mine shaft opens up in the floor of the museum, it only accelerates the nibbling temporal decay that threatens every structure. At last, dramatically, dust and rubble irrupt, sweeping over the scene.

The Johannesburg Art Gallery is a symbol, for Kentridge, of the time of his childhood. Beyond this, it represents a larger history of South Africa and its mining industries. Founded in 1915, on the proceeds of mining, as Kentridge tells the story, the museum was intended as a gesture of atonement for the wealth that colonialism expropriated from the country.(1)

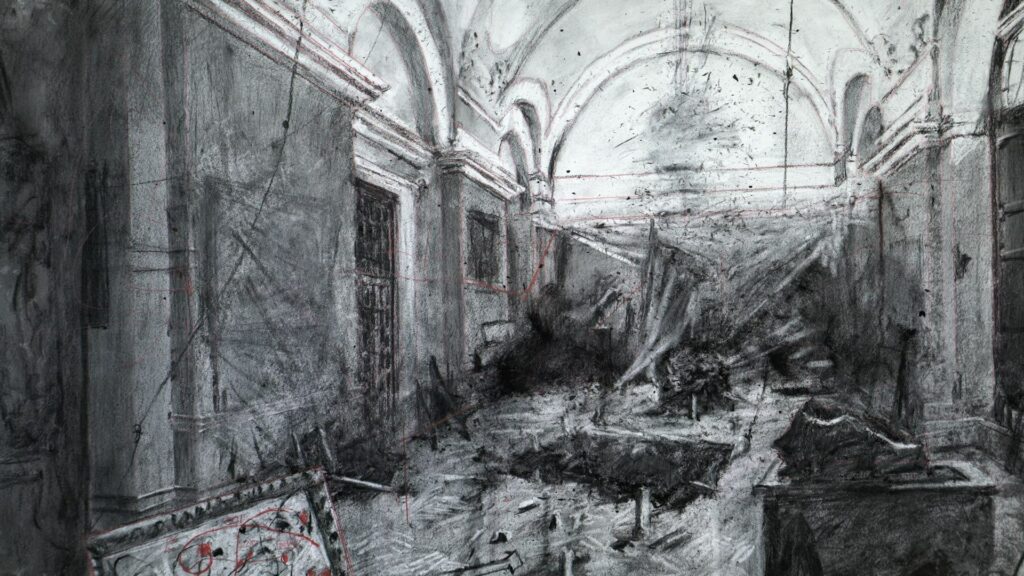

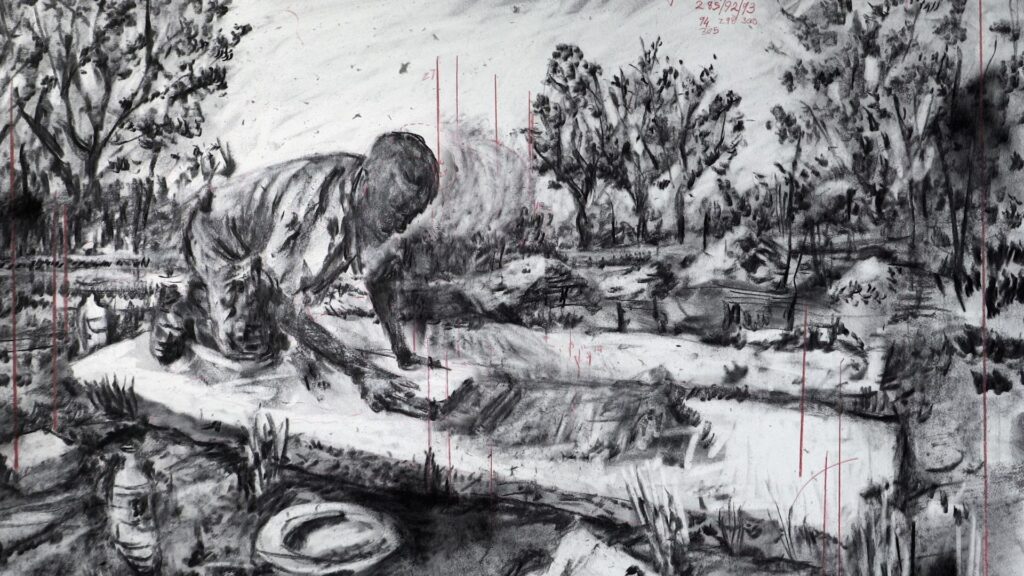

Far from remaining static, however, or functioning perfectly to preserve past time, the museum is now shown falling apart. In the post-colonial ruins, we see figures signifying what Kentridge has described as the «desperation» of the contemporary moment: Zama Zama («try your luck») illegal miners, furtively working in abandoned and disused mines.(2) One such miner is pictured on hands and knees, grinding rock so it can be panned for gold, his repetitive, back-and-forth, upper-body movements seeming to mirror the movements we know structured the artist’s process: rubbing out, making marks, and rubbing out again.(3)

City Deep, 2020, Film still, Courtesy of the artist

Whilst we might at first draw back from such comparisons between the artist’s work with the back-breaking labour of the miners, City Deep itself raises the question for our consideration: showing the mining magnate, Soho Eckstein, who is a recurring character in the Drawings for Projection series, in the museum, looking at artworks, which change under his eyes into allegorical figures and billboards bearing mysterious questions, before becoming scenes and faces from the outside world of contemporary South Africa. What is the work of the artist, compared with that of these other men and women? These scenes stage the gulf between their experience, but also raise the question whether the work of art can connect subjects positioned differently by race, class and gender. More widely, in these sequences, Eckstein offers a stand-in for our own activity as viewers, as we contemplate Kentridge’s art, asking what it means, and how we find the world around us, re-presented here.

The work of the German art historian Aby Warburg provides a framework we might use to understand the kinds of echoes of bodily gesture Kentridge explores, from body to body, across time and place. Warburg’s project was the product of an age that had «lost its gestures», Giorgio Agamben has argued.(4) In particular, his Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, begun in 1924, and worked on until his death in 1929, attempts to make reparation for this loss: compiling a visual history of gesture as a vehicle of the transmission of historical experience.

Core to Warburg’s theorisation of the content encoded in gesture was the idea of supressed, agitated movement. In his 1893 essay on Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, it is «accessory forms in motion» that belie the animating tremble of past time embedded in the figure of the nymph, and signal the presence of the past, surviving within the image.(5)

This sense of the image trembling on the threshold of movement is certainly appropriate to Kentridge’s drawings. The movement they indicate flows both forward and back: on the one hand each drawing points back, as «stills» from the moving film they reference; on the other, the series gestures «forward», toward the reconstruction of the «flow» from which the images were taken.

In its temporal leaps and discontinuities, Warburg’s archive disrupted the idea of «tradition» as peaceful inheritance, proposed by nineteenth-century European historiography.(6) Instead, through its technique of montage, it constructed a model of historical time in which we witness repetitive cycles of violent reoccurrence: the past irrupting in the present, again and again. The atlas was constructed in hope that through the study of images, including paintings alongside newspaper photographs, we might come to understand, rather than merely repeating, past events. As such, Agamben proposes Warburg’s work as both symptom and attempted cure for what has come to be known as «biopolitics»: the emergence over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries of a regime of power that is focused on the ever more precise administration and control of bodies; a regime to which the project of European colonialism was foundational.

Like Warburg’s Bilderatlas, Kentridge’s art, too, was formed by his struggle to understand the appearance of the past in the present. Despite the fact that Apartheid came into being in South Africa only in the immediate years after the Second World War, and Apartheid legislation was not repealed until 1991, with the first free elections in South Africa held in 1994, for Kentridge and other white, anti-Apartheid activists of the time, it seemed almost impossible to come to grips with the contemporaneity of Apartheid; they were plagued by a feeling that they were living through a repetition of past historical events.(7) This was of course, an illusion. Apartheid was a political and legislative programme responding to precisely contemporary pressures: in particular, the influx of the black population into urban centres, displaced from farms, as the South African economy changed after the war. Apartheid was brought into being in an attempt to arrest or prevent social and political change, in the face of such historical movement.

City Deep, 2020, Film still, Courtesy of the artist

Perhaps for this reason, the sense of living through a moment of the «past» could be subjectively overwhelming. Kentridge has spoken of reading the work of Frankfurt School philosopher, Theodor W. Adorno at this period, and contending very personally with his statement that «there can be no lyric poetry after Auschwitz». He describes this as leading to him ceasing making art for a period as a result: «At that stage in the mid-1970s, we were struggling to think through what images needed to be made… What is to be done? What needs to be made? That’s one of the reasons why I stopped thinking of myself as someone making images for several years, because I couldn’t answer that question.»(8)

The sense of inescapable historical repetition is one that can overwhelm the subject’s capacity for action, as it comes to seem that the immediate events around them have in some sense already happened, or are predetermined, and their own historical presence is in some way shadowy, almost like that of a historical ghost. This is sometimes how Kentridge’s figures appear; haunting the landscape, present for a moment and then gone.

And yet, against this sense of incapacity, in City Deep, I want to propose, Kentridge offers us the figure of the miner – under pressure from forces of erasure – as an exemplary model for the work of the subject caught in history. As he hammers rock, digs earth, or sifts fragments for gold, we are offered a figure for the labour of the artist; and beyond that, our own effort, to understand our moment in time.

In her 1954 essay, «The Gap Between Past and Future», the German philosopher Hannah Arendt tells a parable by Kafka. Opening without preamble, Kafka’s story, called simply «He», reads like this: «He has two antagonists: the first presses him from behind, from the origin. The second blocks the road ahead. He gives battle to both. To be sure, the first supports him in his fight with the second, for he wants to push him forward, and in the same way, the second supports him in his fight with the first, since he drives him back. But it is only theoretically so. For it is not only the two antagonists who are there, but he himself as well, and who really knows his intentions? His dream, though, is that some time in an unguarded moment – and this would require a night darker than any night has ever been yet – he will jump out of the fighting line and be promoted, on account of his experience in fighting, to the position of umpire over his antagonists in their fight with each other.»(9)

Something about this passage seems apt for what Kentridge pictures. These are bodies on which forces visibly, materially press. There is a sense of material flux in these drawings and animations, in the inky blackness which seeps out of the corners, and blooms across the surface, threatening to engulf the figures – from which, nevertheless, they emerge, to step forward, and back, and forward again, into the historical murk.

Arendt’s use of the Kafka fable points to the small hopefulness afforded by our own physical existence: our insertion into time creates a «small non-time-space in the very heart of time», she says.(10) Arendt insists that this small space of action is incomplete unless it is occupied by reflection. «Only insofar as he thinks… does man in the full actuality of his concrete being live in this gap of time between past and future.»(11) It is the activity of thought that «paves a path» between past and future, by means of which, «the trains of thought, of remembrance and anticipation, save whatever they touch from the ruin of historical and biographical time.»(12)

City Deep, 2020, Film still, Courtesy of the artist

This we may think is the space of the image, as Kentridge constructs it. This is the space for reflection his drawings afford, in which historical struggle is (re-)inscribed and remembered. The lesson that Kentridge’s work extends, is to learn to see both what is the same and what is different in the darkness of the historical moment that confronts us: to pave the path of thought between our own and others’ experience, and between the past, the present and a future that is still to come.

–

Tamara Trodd lectures in modern and contemporary art at the University of Edinburgh. She is the author of The Art of Mechanical Reproduction: Technology and Aesthetics from Duchamp to the Digital (Chicago, 2015), and Screen/Space: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art (Manchester, 2011). Her published essays focus in particular on photography and film, including, most recently, «WELCOME! Elizabeth Price and the Life of Objects», Art History (May, 2019). She is currently working on a book about the relationship between the 1930s and the present day, via a series of case-studies on projected-image art.

1 William Kentridge, interviewed by Aimee Dawson in The Art Newspaper, 6th October, 2020, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/interview/william-kentridge-city-deep, accessed November 16th, 2020.

2 Kentridge, The Art Newspaper.

3 Information about the film supplied by the artist’s studio.

4 Giorgio Agamben, «Notes on Gesture», in Means Without Ends: Notes on Politics, trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p. 49.

5 Aby Warburg, «Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Spring» (1893), in The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity, introduction by Kurt W. Forster, trans. David Britt (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1999), pp. 89−156.

6 See Georges Didi-Huberman, «Artistic Survival: Panofsky vs Warburg and the Exorcism of Impure Time», trans. Vivian Rehberg and Boris Belay, Common Knowledge, vol. 9, issue 2 (Spring, 2003), pp. 273−285.

7 «William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland in conversation with Tamar Garb, July 2015», in Tamar Garb et al., William Kentridge, Vivienne Koorland: Conversations in Letters and Lines (Edinburgh: Fruitmarket Gallery, 2016), pp. 118−145.

8 «William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland in conversation with Tamar Garb, July 2015», p. 120.

9 Hannah Arendt, «Preface: The Gap Between Past and Future» in Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought (New York: Penguin, 2006 [1961]), p. 7.

10 Arendt, «The Gap Between Past and Future», p. 13.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.