Interview with William Kentridge

Zurück

Making Sense of the Non-sense of the World

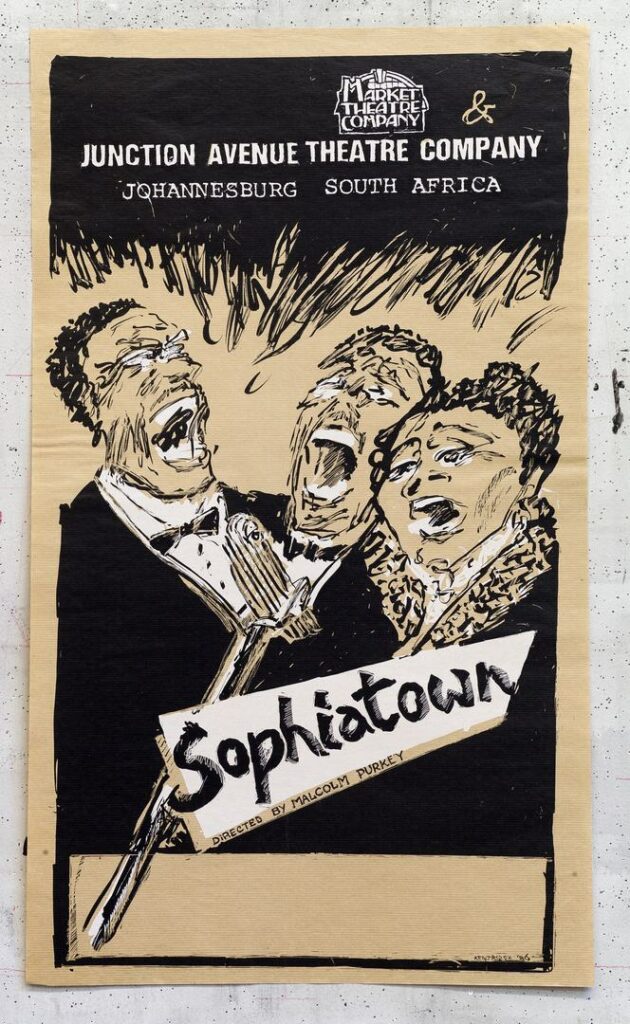

Suzanne Cotter: William, having trained as an artist, you first began working in theatre as an actor and also as a director in the mid-1970s with the Junction Avenue Theatre Company in Johannesburg. Around the same time, you began making short experimental films and working with printmaking techniques. Did you know then that working within the realm of theatre would be something you would sustain alongside your development as a visual artist?

William Kentridge: In the 1970s at university where I was studying politics and history, I worked both with a student theatre group but also went to evening lessons and part-time lessons at the Johannesburg Art Foundation. At that stage, I was doing both without expecting to be either an artist or an actor. I thought I would get a profession, be an engineer, or an architect, or a lawyer, get a real job at some point. And then I was advised that one needed to focus on one thing, even though I still didn’t know what that would be. I followed this advice and I gave up my studio and studied theatre in Paris with the idea of becoming an actor and leaving the art world. And I failed at being an actor. I came back and tried to be a filmmaker and didn’t succeed at that. So, I was reduced in the end to being an artist. Again. And only years later, in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, did I discover that I was making films and also working in

theatre as well as drawing.

Sophiatown, 1987, Poster, Courtesy of the artist

SC: You have said that you learned more about drawing through theatre than from art school. Could you talk about this?

WK: I think that what I learned in theatre school is the importance of the movement of the body. So that, for example, if you’re doing a drawing, you can either think of it as a movement from your knuckles, if you’re doing a fine drawing, or from your wrists if it’s slightly larger, or from the elbow, or from the shoulder, or from the whole body. What the theatre does is that it gives a very strong focus on what is the meaning that comes from the movement of the body. Where does a gesture originate, and what is its logic? What is the impulse you need behind a gesture? Either a gesture as a physical gesture in theatre or a mark that you’re making on a sheet of paper. So, with understanding drawing as a kind of record of the movement of the artist is something that really comes from theatre rather than from art school.

SC: In your drawings and your Drawings for Projection, and in recent years, your performances – I’m thinking of the Ursonate or your collaboration with Joanna Dudley on A Guided Tour of the Exhibition: For Soprano with Handbag, or your drawing lesson films which you began making in 2009 – the body as a protagonist, the body of the artist in the studio, are always implied. How did your time in the early 1980s as a student at Jacques Lecoq School of Mime in Paris impact this way of thinking about the body and using the body as a tool?

Berlin Memory 3’14“, Ref: 7/06/2016 (Drawing Lesson 49), 2016, Film still, Courtesy of the artist

WK: The theatre school was a school of movement. It was not the English style of acting, which starts psychologically from the text outwards. This was a theatre without text. It was about all the metaphors of movement inherent in the body. Do you move like honey? Are you moving like clay? Is there a great tension? Is there a lax tension in your body? What do the different diagonals and the angles of the body mean? Which are graphic questions, always. What is the tension in your hand while your hand draws? What is the relaxation? How do you approach a sheet of paper and step back from it? It understands that the activity of art making is very much a record of what the body does. And that, for me, was and still is very, very important. But also put the other way, that the processes of drawing, the activity of making the drawing, also the activity of working out what the drawing will be, is a good way to think of theatre, which is reverse of the way it is usually thought of. We usually start from an idea or a text and work out a production from it. Here it’s arriving at a text maybe at the end, but not beginning with it.

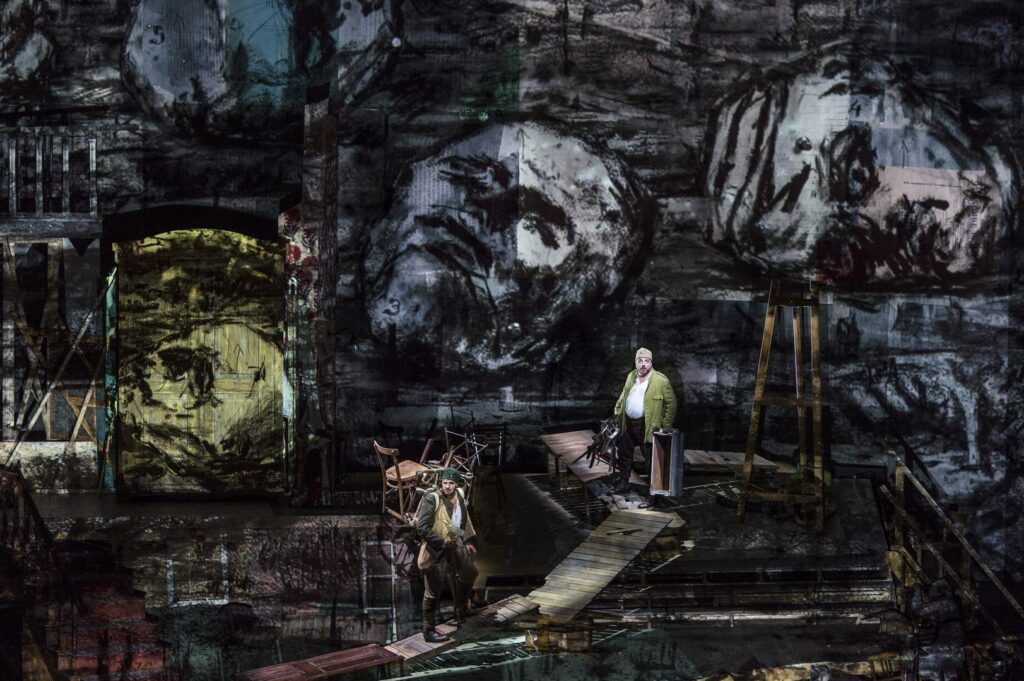

Wozzeck, Salzburger Festspiele, 2017 © Photo: Salzburger Festspiele / Ruth Walz

SC: During the 1990s, as you gained increasing international attention for your work, your dialogue with theatre and performance remained fairly constant. Could you talk about how the visual language of Drawings for Projection made in the studio, using the processes of stop-start filmed animation, was inspired by your collaboration with the Handspring Puppet Company, and your production with them of Woyzeck on the Highveld and, some years later, Faustus in Africa!?

WK: Yes. In the late 1980s, in 1989, just at the time when the transition to democracy in South Africa was beginning, I started the first in the series of charcoal animated drawings. And a year or so later, I made contact with the Handspring Puppet Company, or they with me. I’d known their puppet work and they’d seen some of my animations, and we thought: What happens if we put together the world of puppetry, which is an artificially constructed set of actors, with very artificial landscapes that are drawings and not films? There’s something of a similarity of a carved puppet to a charcoal drawing that made the combination seem possible. So we started with the production based on Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck in 1991/92 and over many years did several productions together, ending up with the opera production of The Return of Ulysses in 1998, but including productions of Faustus and Alfred Jarry’s Ubu.

SC: Since being commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera in New York in the 2000s to direct Shostakovich’s opera The Nose based on a libretto by the Russian author Gogol, you have directed and designed operas that have been performed at some of the most important opera houses in the world. To name some of these works: Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Alban Berg’s Lulu and Wozzeck. This operatic dimension is also coming to the space of the museum. I’m thinking of your epic production of The Head & the Load which takes as subjects the million Africans who worked as porters in World War I and the paradoxes of colonialism. The work was presented in the Park Avenue Armory in New York City, and in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in 2018.

Could you talk about the process and constancy of certain themes alongside the interchangeability of the mediums and forms within your transdisciplinary oeuvre? Can we talk about a Kentridge language?

WK: I’m not sure if we can talk about a language. I think of it as a lack of imagination. The same images come back again and again. The megaphone, the rhinoceros, the typewriter. Images like that. But they’re used a bit like Commedia dell’arte characters to perform different stories or different narratives. There are elements in The Head & the Load, which as you said is about African porters during World War I. It’s a historic piece about history. But it also uses the technique of processions, large-scale shadows that I’ve used in several other productions and artworks, like More Sweetly Play the Dance which will be shown at Mudam. There’s often a migration, a translation from one medium into another. A theatre production will suggest a suite of etchings, the etching will suggest another dance performance. It’s hard to say which is the final resting point. They’re all provisional. You can think even of the animated films that the drawings are made from in the service of making the animated films, the series of sixty drawings or thirty drawings that are usual to make a film. There are always in the suite of drawings, drawings that would never have arrived if I was not making the film. So the film also is an agent for producing other works. You can also see the film as a very complicated recondite way of arriving at a suite of drawings. So it goes back and forth, and I don’t necessarily think of one as the final endpoint and the other as an intermediate stage. But the sense of drawings in the service of other forms, whether it’s theatre or film, is quite strong. It brings a kind of ease to the drawing, now that they’re provisional and don’t have the kind of weight of an oil painting that would be considered and reconsidered, and worked and reworked, until it’s finally there. It’s a final statement. The drawings, or all the works, are a provisional moment in the making of something else.

SC: Collaboration is also a constant in your work. The programme for the red bridge project in Luxembourg is the result of numerous collaborations, many ongoing, with musicians, composers, dancers, singers, cinematographers, and others. I’m thinking of the Handspring Puppet Company on Il ritorno d’Ulisse, your work with composers Philip Miller on Paper Music, François Sarhan on Telegrams from the Nose, Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd on Waiting for the Sibyl, and soprano Joanna Dudley on A Guided Tour of the Exhibition: For Soprano with Handbag, as well as your collaboration with dancers Dada Masilo or Thulani Chauke, and with set designer Sabine Theunissen, to name only a handful. There is also your ongoing collaboration with the Centre for the Less Good Idea – the Centre will lead workshops as part of a residency at the Grand Théâtre in the context of the red bridge project. Is it fair to say that collaboration is a defining aspect of your creative process?

Video still from film made for More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015, Courtesy of the artist

WK: Yes. There’s usually a kind of a wave. After working with many people on a project like The Head & the Load or More Sweetly Play the Dance, which might involve twenty, or thirty, or forty people for an extended period of time, there’s a real pleasure in being on my own in the studio and making drawings, just me, no one else. But after a while of doing that, I kind of long for the company, and the excitement, and the productivity of working with many other people together on a project. So both are important. But collaboration certainly has been important. If it can’t be made with just charcoal, and wax, and sticky tape, then I need a collaborator, whether it’s with an etching or with a sculpture. I need the assistance of the foundry. I need the assistance of the printmakers. I work with editors all the time. The conversation around the work as a way of understanding what it is that I’m doing is central.

SC: Your theatre collaborations during the 1990s reflected closely on the political events of the time in South Africa with the end of Apartheid and the transition to democracy that you mentioned earlier, the liberation of Nelson Mandela, and the beginning of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I’m thinking of the stage production Ubu and the Truth Commission, and your drawings and filmed animation Ubu Tells the Truth. How does the history of South Africa relate to the programme of performances and stage works for Luxembourg, if at all?

WK: It’s always, there’s always a connection, even if the ostensible subject is not specifically South African. The works, apart from Telegrams from the Nose, which is made by a European music ensemble, all the work is very inflected by Johannesburg through the drawings and through the sensibilities of the collaborators, of the musicians, of the performers, of the dancers. Paper Music, even though it has one singer based in Berlin, and one from Johannesburg, and a pianist from Italy, it’s very much a Johannesburg work for me. In the sense of the drawings and the subject of the films, of the songs like the «Lullaby for a Burglar Alarm» is very much a Johannesburg song about sleeping so happily through the sounds of all the burglar alarms going off in the suburbs, just because they’re so used to that sound. So, a lot of things are very located in South Africa. Some of the work is more specifically related to political moments, like The Head & the Load about Africa in World War I and questions of colonialism. Even with the Ursonate, which to perform is not specifically South African – it was made by Kurt Schwitters – the sense of the questions of intelligibility and unintelligibility, and the importance of the absurd as a category, for me relates very strongly to what it is to grow up in the absurd state of Apartheid in South Africa, where one finds a logic that no longer holds. So even if the work is not about South Africa, there is South Africa in the work.

SC: Several of the works in the programme for the red bridge project draw upon classical mythology such as Homer’s Odyssey or the Cumaean Sibyl. What is the role of allegory for you, both in terms of narrative in your work and in relation to the act of making?

WK: I suppose there always has to be a meeting in the work between a theme that intrigues me, or interests me, or a riddle that it poses, and the medium through which one can think through that question. So, Sibyl, it’s both about the myth of the Sibyl from Classical Antiquity, but it also has to do with the pleasure of drawing on pages of books and thinking of pages as leaves, leaves of a book and leaves of a tree. There was a meeting of a kind of a classical mythology of the Cumaean Sibyl and the medium I was working on, ink on found pages in the studio. There are things in Ovid’s Metamorphoses that are specific about transformation, which is the same kind of terrain as animation. They’ve always intrigued me. But also, of metamorphosis being the result of fear or panic. So that brings it back to more urgent questions. Even if the form is one of classical mythology, the questions that generate that panic can be much more local and contemporary.

SC: Can you talk about the invitation from the Rome Opera to create what became Waiting for the Sibyl?

WK: Yes, Waiting for the Sibyl was an invitation from the Rome Opera to do the second half of an evening. They were reviving a production from 1968 by Alexander Calder, which is an eighteenminute piece he made for Rome Opera to Italian contemporary music from the 1960s, and some of his mobiles and cyclists riding around the stage… A very minimal, very beautiful piece of work. And we made a separate piece, a forty-minute chamber opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, which visually has various references back to Calder’s production, particularly the sense of the leaves circling around the tree, the wind blowing the leaves around as an echo of some of Calder’s moving mobiles. There was a formal connection, but then a parting of ways, and it became its own project. Very often, one starts with a very specific impulse, in this case looking at the Calder, and then the work takes on its own logic. And in fact, one then can almost remove that first impulse and the work then stands on its own and will provoke other connections. So, in Luxembourg, we don’t present the Calder work. It’s not ours to produce – it is controlled by the Calder Foundation. But we have a different first half of the programme, which is an expansion of the film City Deep. And it uses the same musicians that we use in Waiting for the Sibyl. So it’s a kind of a prelude to the opera, which is very much about fate and mortality.

Workshop for The Head & the Load, Johannesburg Studio, 2017 © Photo: Stella Olivier

SC: Where we are now, entering into the third decade of the twenty-first century, the elusiveness of our future seems all the more resonant. In many of your works, you address different notions of time: historic time, colonial time, and the impossibility of being in time in multiple worlds. How important is it for you that your art speaks to the time of the present?

WK: I don’t know if it speaks to the time of the present. Hopefully, people watching the work will find connections or echoes, or recognitions of things that are happening. More Sweetly Play the Dance was made at the time of the Ebola epidemic in Africa in 2015/16, but obviously it has strong echoes, images of sick people, of people in hazmat suits, the images we’ve all seen so much in the last year with Covid-19. So there are echoes that jump out. I think we’re very good at making connections, finding links between things that we see or hear and who we are. So even if something’s set in a completely different country, set in South Africa, someone in Romania might say, «Oh, that feels completely local». And that’s because of our desire to make connections across different contexts.

And our inability not to make connections runs even more strongly. It’s part of what it is to be human, to be looking to solve the riddles, which come towards you from the world.

–

Suzanne Cotter is Director of Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean. Previously Director of the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto, she has held curatorial positions at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York; Modern Art Oxford, UK; the Hayward Gallery, Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the Serpentine Gallery, all in London. She has curated over 100 exhibitions with contemporary artists from around the world and overseen numerous artist commissions. In 2005, Suzanne Cotter was made Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France.